Henderson Street, Leven

I hadn’t long returned as editor of the East Fife Mail, based opposite the Caledonian Hotel in Leven’s Mitchell Street, a stone’s throw from where I grew up.

It was a sort of homecoming and, for a while anyway, seemed the right fit. Having grown up in the town everything felt very comfortable. As a youngster I stood outside what was now my office listening to the clicking of the typewriters. My mother had taught at the secondary across the road, the Jubilee Theatre was one of my playgrounds, right on the borderline with the posher part of Leven – Links Road.

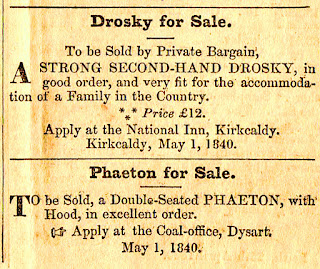

A cafe hadn’t long opened a couple of doors up from the Mail and had a few old framed photographs on the wall. One lunch time I popped in, probably for soup, and while I was waiting to be served I had a good look at these pictures. One leapt out at me – Henderson Street.

Now long demolished, this little street had made a huge impression on me. While the Jubilee and Mitchell Street were 50 or so yards to the east of where we lived in Rosebery Terrace, the same distance to the west, or thereabouts, was Henderson Street leading to the Shorehead.

My best pal Vic Pilka stayed between the two in South Street so I probably made at least four journeys a day down this last remnant of ‘Auld Leven’.

Even as a child, it felt as though it was from another time. If you look at the picture, the house at the far end with the two windows was, in my time, the home of Ella Meek, the leader of Leven lifeboys.

Although you can’t quite make it out, between the gable end of her house and the start of Henderson Street there was a single lane track – one wide enough to accommodate a 1967 Triumph Herald trying to out-run, outwit and out-manoeuvre the police: more of that later.

Just behind the corner on the left side of the Henderson Street houses was the entrance gate which took you to the rear of the properties. As a youngster you really did have free rein to venture just about anywhere in your neighbourhood, especially in the common areas of Viewforth Square, the back of Viewforth, Buchlyvie and, of course, Henderson Street.

It was typical of the usual square set-up with individual areas divided up for the houses, just across from a communal path and the coal bunkers. Some had been kept as low maintenance drying greens, others had well-tended flower beds and, just as you came in the gate there was a wire-mesh aviary which was also probably a pigeon coop.

I don’t ever recall becoming too familiar with those ‘plots’, probably because I don’t think there was an exit at the top, so I always tended to use the road in the front of the houses.

That all stopped I would reckon when I was around eight or nine years of age. I’d been out playing and came home for my lunch, soup and pudding at the table in the living room. However, there was a bit of a scene that greeted me this occasion, with a worried and stern-faced mum and dad anxiously awaiting my arrival.

They’d had a visit from a mother and daughter from Henderson Street. The mum has come to warn my parents that I could never venture near Henderson Street again as her husband had vowed he would “kill me”. The reason for this terrifying threat was that I had killed all the birds in his aviary, with an airgun, and not only that, the daughter had seen me do it.

My parents protested my innocence, the police weren’t involved but I was warned off – for all time.

As a youngster I don’t know how all this panned out among the adults but I do know the wee girl, who I have a vague recollection of being a couple of classes above me at Parkhill, was adamant that she saw the bird killer and that boy was me. Of that, she was in no doubt and totally unwavering in her testimony.

I can’t recall how many birds were slaughtered and while there is no way I would harm one of God’s creatures, not then or now, there are certain aspects of the alleged crime that still bother me to this day.

Firstly, I have never possessed an airgun. In fact, the only time I have fired one would have been at the shows on the Prom when they were chained to the counter. The target then was either a wee tin can shape, each in an individual alcove, or a row of dented ducks on a pulley. The showman had to load the gun for me as I could break it for loading, and then I was a lousy shot, failing to come even close to ever winning a gonk.

So … hitting a veritable flock of birds would have acquired a great deal more marksmanship than I possessed if I had owned or had access to a gun, and would surely have taken quite some time? Also, this was at the back of a row of houses; surely someone would have seen the assassin (other than the daughter of the bird owner!) and stopped him, or her? Plus there would have been the repeated crack of the rifle and the frightened squawks of the fowl.

No. This was a frame up, though the reasons to this day still bewilder me.

Some time later the lass crossed my path on the road between Woolworth and what was then Cook’s highly flammable furniture store, whose subsequent blaze, I hasten to add, saw no blame attributed to me! I asked her why she had said I’d shot all those birds, and she took to her heels, screaming she was going to get her dad.

So my detours around Henderson Street continued. Vic moved up to Scoonie and the bulldozers moved into the area. Henderson Street didn’t fall immediately. The rear was demolished, the residents relocated and it became a grim and depressing wasteland of rubble.

Re-exploring it I made the acquaintance of an old tramp who camped there and always welcomed me round his wee fire and regaled me with his tales of life on the road. You can’t imagine anything like that happening nowadays, and I’d be beside myself if my grandchildren disappeared to spend time alone with a homeless stranger. But I thought nothing of it, he was kind and funny, and I remember being sad when he just up and left without saying a word.

That nearly ends my connection with Henderson Street, but not quite, at least not with that lane that ran down the side of it.

One night, having not long bought my first car, a quite beat-up 1967 Triumph Herald, I drove my pal home to Methil. On the way back to Leven, I attracted the attention of the boys in blue and found a police car sitting very close to my tail. There was no flashing light just the psychological tailgating.

At one point I pulled over to let them pass, but they just stopped a short distance behind me and waited. When I pulled away, they came too. By the time I crossed the Bawbee Bridge and was nearing home, my unease started to give way to what I suppose would have been adolescent arrogance, so I decided to give them the slip.

This was my backyard.

A couple of changes of gear and speed, though always within the limit, and I dropped down that lane and on to School Street, nipped to the end, took a left into Forth Street, then another to the wall at Rosebery Terrace and my back door.

Having just parked and opened the car door, I was suddenly caught in full beam, and by the collar. One of the officers heaved me to the front of the vehicle and slammed me into the wall. As I thudded into that, I could see my mother’s face peering out the scullery window, and then the light as she opened the back door.

The policeman, obviously having watched too many American cop shows, then heaved me across the bonnet of the Herald demanding to know what I was doing, where I stayed, whose car it was.

I tried to tell him this was where I lived, but he was having none of it.

Just then, I heard a loud, “What’s going on here?”

I managed to twist my head from the policeman’s grip to see mum in hairnet and candlewick dressing gown.

“Do you know this boy?” the officer said.

“That’s my son,” said mum. “He lives here. What’s he done? He was just dropping his friend off.”

There was an awkward pause.

“There’s been a lot of car thefts ma’am,” said the policeman. “Just making sure everything was in order here.”

And at that, they were off.

And that really does end my connection to Henderson Street. So seeing the picture in that cafe brought back all those memories. I asked if I could have a copy of the photograph, but the owner refused. I then asked if she would allow me to take a picture of the picture! But she refused me that as well.

I even carried a small piece in an edition of the East Fife Mail, asking if anyone had a picture of Henderson Street, to no avail.

Then, an appeal on the Facebook page, Auld Fife & Its People, duly brought Henderson Street back to life, and, to this day, it still remains one of my favourite pictures.